The Longevity Revolution. We're not ready for how rich we will be.

You can live longer and get richer than you thought possible. You need to think differently about investing.

A Quiz of Your Investing Intuition

Are you up for taking a one-question quiz? This will test your intuition of compound interest.

You’ve likely seen a compound interest chart, a curve that bends upward, showing investments grow faster over time. Like this:

Now read this scenario. Guess the answer without doing the math or reading ahead. Just go with your intuition.

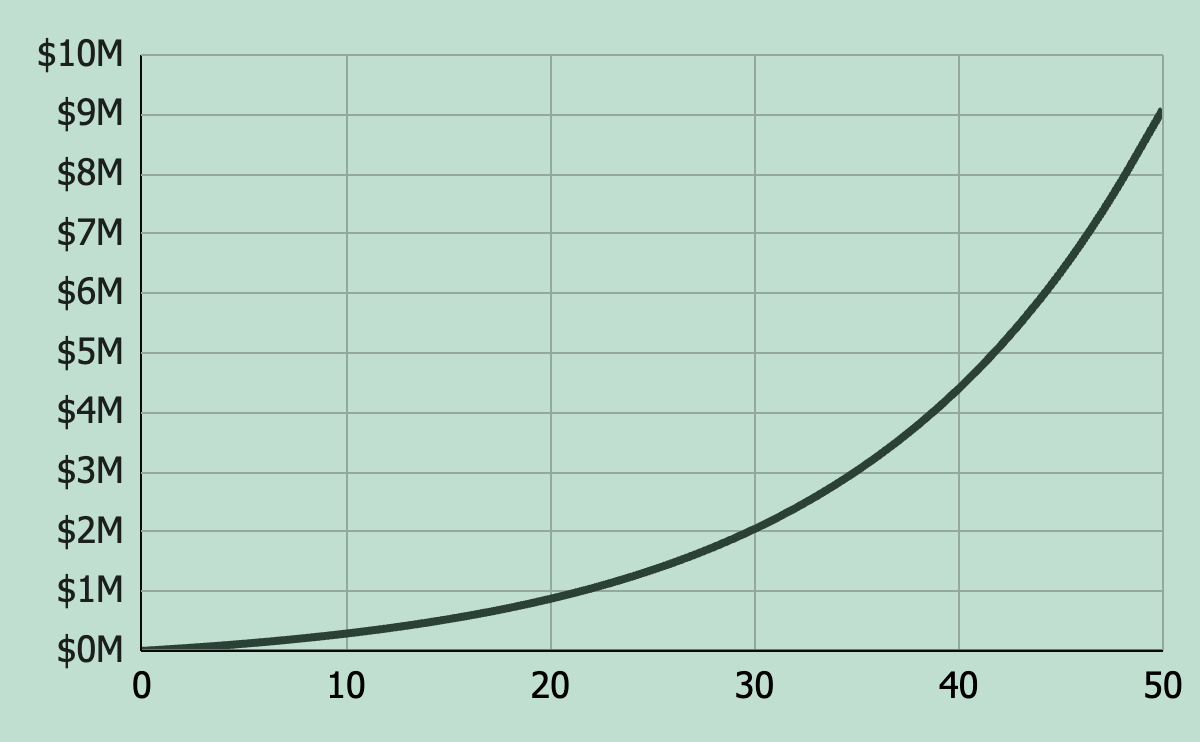

Scenario: Let’s say that Sara makes $100k per year and invests 20% of her pay. We’ll assume inflation-adjusted returns of 7%.

That means it takes Sara 22 years to accumulate her first $1M.

Quiz: At this rate, how long does it take Sara to accumulate the second $1M?

“The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.” — Albert A. Bartlett.

Do you have your guess? Is it twenty years, fifteen years, twelve years, ten years? Less? It’s actually eight years. It took Sara twenty-two years to earn the first million. She earned the next million 3x faster.

The problem with our intuition is that it tends to underestimate exponential growth. We’re not used to it. Things tend to change linearly in the physical world. If you run twice as long, you go twice as far. But, with exponential changes, if you invest twice as long, you have ~5x more.

What was your guess to the quiz? I’d love to see your guess in the comments.

Longevity = Time. Time = your biggest asset.

Living longer, healthier lives will amplify investment compounding.

If Sara continues to invest similarly for 50 years, she will end up making $1M every 18 months! That’s the tip of the iceberg if she lives to 100.

Despite this, longevity has traditionally been considered a risk in financial planning: the risk of outliving your money.

How can that be true when the benefits of compounding increase with time? It’s a half-truth, and we need to update our investing frameworks with the full picture.

Living to 100 can 3x your portfolio

The human longevity revolution is exciting. It’s not clear whether it’s here yet or a decade or two away, but it is clear we are on the cusp of a new wave of healthcare advances and treatments that can potentially increase lifespan. We already have new treatments like immunotherapy for cancer and GLPs for metabolic diseases. All sorts of other1 cool2 things3 are on the way4.

There’s a lot of optimism. Stanford University’s Center on Longevity believes “In the United States and beyond, 100-year lives will be common for those born today.”5

Will I live to 100?

Reading about longevity made me start to wonder what it means for me and my investment strategy.

That question led me down a rabbit hole of actuaries’ tables and statistical models as I tried to answer one question: How likely was I to live to 100?

The most helpful resource I found was the American Society of Actuaries Longevity Illustrator tool. It combines your age, sex, Social Security data, a rough health adjustment, and projected longevity gains.

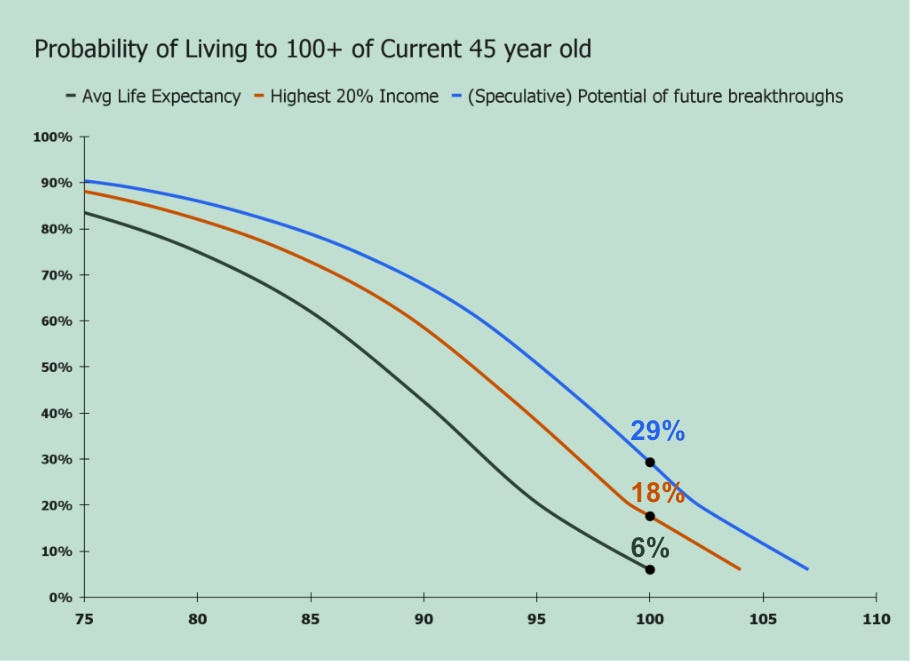

I learned, however, that the tool doesn’t consider one major predictor of longevity: money. A JAMA study found that people in the top 20% of income live about +4 years longer than average6. Shifting the longevity curve by +4 years turns out to be huge. W already know that lifelong investors can reliably reach the top 20% of wealth, even if their income starts small.

I wanted to take an optimistic view of longevity, so I added a scenario with +3 extra years from possible medical breakthroughs in my lifetime. Granted, this is a pretty speculative guess.

Probability of living to 100, the numbers

Here are the results of my simple math7 for a 45-year-old in average health:

6% living to 100 for current actuary estimates

18% for adding +4 years for high income. Nearly 1 in 5.

29% for high-income individuals and assuming 3+ years for medical breakthroughs. Approaching 1 in 3. (Speculative)

I’ll be mildly optimistic and call it a 1 in 4 chance to reach 100. Not bad.

Now let’s see what that means for investing.

How does a 100-year longevity affect our investments?

Warren Buffett has likened his wealth growth to a snowball. He said, “I started building this little snowball at the top of a very long hill. The trick to have a very long hill is either starting very young or living to be very old.“ Buffett did both.

You don’t need to beat the market to have above-average results. You just need to stay in the market for an above-average amount of time. A few examples illustrate this:

Example #1: Warren Buffett, mogul

It turns out that Warren Buffett made 99% of his money after age 50. Not a typo. I fact, Warren Buffett didn’t cross the $1 billion mark until age 56. He is now 95 and is worth $150B.

Buffett got rich because he is a great investor. He got fabulously rich because he was a great investor into his 90s. His last $100B was simply a matter of investing a very long time.

Example #2: Grace Groner, secretary

In the 1930s, a young secretary named Grace Groner bought three shares of Abbott Laboratories for about $180 total. That was it. She never sold. She simply reinvested dividends for the rest of her life.

When she passed away at 100 in 2010, her family was shocked that those three little shares had quietly multiplied into over 100,000 shares, worth over $7 million.

Example #3: Sara, our hypothetical saver

Let’s return to Sara. We’ll assume she works for 40 years, retires at 60, and lives to 80. She wants to live it up, spending $200k/year in retirement.

If she lived to 80, she would die with about $8M. Not bad

If she lived to 100, she would die with an inflation-adjusted $22.5M or 3x more!

Important note - Sara is investing 20% of her salary. That’s the minimum to let compounding do its magic. Saving more would obviously get you there faster. So if you aren’t there yet, start working through this step-by-step guide.

Avoiding Wealth Traps

Now that we’ve seen the upside of living a long time and how much compounding can impact later years, let’s look at some traps that pop up.

Of course, no one should cry over your extra million, but thinking ahead can help prevent some thorny issues.

1. You will need more high-growth investments in retirement

Most financial advice treats longevity as the risk of outliving your money. That’s true within the traditional investing framework. In the traditional view, you should move to safe investments in retirement to protect your wealth.

But longer timelines call for a different framework. Rather than focusing on protecting wealth, your mental model should be how to manage the risk that your portfolio may not grow sufficiently.

Your portfolio needs to outpace your spending and inflation, which means more equities later in retirement, while still managing sequence of return risk. A standard 60/40 portfolio won’t deliver enough growth to last 50+ years. You need a glidepath that reduces equities around retirement and then increases them again.

2. You should wait to take Social Security

Social Security becomes even more valuable the longer you live. It’s the one annuity that is indexed to inflation and you get as long as you live (with some survivor benefits.

There is a lot of debate over whether to take Social Security right away or wait until age 70 for the maximum monthly benefit.

The right move for those aiming to live longer is to wait until 70.

3. You’ll need a comprehensive tax plan

Many people default to using a Traditional 401(k) when accumulating wealth. You might assume that if you’re earning a good salary now, you probably will be in a lower tax bracket in retirement.

But if you end up wealthier than you guessed, you could easily find yourself in a higher tax bracket in retirement. This often happens once Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) kick in at age 73, which can lead to tax bombs that cost you $10,000+.

Then there are the tax cliffs to navigate. Medicare’s IRMAA surcharges jump at specific income thresholds, the 0% capital gains bracket is limited, and the interaction between all these different income sources matters. What seemed simple becomes a puzzle that requires detailed planning.

3. You shouldn’t delay living your life.

It’s sadly common to see people with millions in their portfolio still agonizing over whether they can “afford” a nice vacation. They’ve spent so long optimizing their net worth that it becomes hard to switch out of their frugal mindset and start spending on the things that matter to them.

As you accumulate wealth, you’ll also need to think deeply about how you want to use it. How would you live if you had to spend more money? What would you start doing now?

Would you take the whole family on vacation to an Italian villa? Take a career break to learn a language? Sponsor of a local charity? Pay for lessons to finally learn the piano?

Instead of a bucket list of things I want to do when I retire. I have a list of things I want to do before I retire. It helps me 1.) force myself to live now, and 2.) it gives me license to spend while I am still getting a paycheck.

4. You’ll probably have to confront your sense of purpose.

Do you have goals for your next phase of life? Do you know how you want to spend the next 5 to 7 decades of your life? It’s easy to feel a bit lost in this transition. Work gives structure, purpose, and identity.

You should start building other sources of meaning and community well before achieving our financial goals.

It could involve volunteering, mentoring others in your field, participating in local community groups, or engaging in local politics. The goal isn’t to fill every hour of your day, but to have a sense of purpose beyond accumulating wealth.

Live long and prosper.

Today, living to 100 is at least a 1 in 5 chance for middle-aged investors in average health, and the probability is only likely to increase with time.

This can make your portfolio grow astonishingly well, and it can also lead to unexpected wealth traps in your financial plan.

Getting ahead of these will allow you to avoid the mistakes I’ve seen others make. I’ll be writing more in the coming months on managing these particular problems.

FAQ

What if you plan to retire early?

Even if you plan to retire early, most people still work longer than they need to. The extra income will compound dramatically if you live a long time. People like to have extra money. It helps you sleep at night. It helps you worry less about a potential medical emergency or other curveball.

Working longer than planned is something nearly everyone does, and we have a term for it: one-more-year syndrome.

For a similar reason, diligent savers tend to be overly conservative. Most retirees still have 80% of their initial portfolio after 20 years of retirement. I wrote about why we do that here.

But what if you don’t have a high income?

You don’t need a high income. But you do need a few things. You need a high savings rate. You need curiosity and a willingness to learn to invest. You need patience over decades. I also hope you naturally want to get the most out of life.

With these, many middle-class earners have built impressive wealth. These are the people I’m writing for. I think that’s probably you.

There is, of course, a dimension of luck in all things. Most of all, health. A serious diagnosis for yourself or a loved one can, sadly, derail any life and financial plan.

Lastly, the market has to stay on track, over the medium and long term. (Although with valuations so high, and the risk of stagflation rising, some dark clouds are growing on the horizon.)

The odds are more in your favor than you realize.

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-10-enzymes-weaken-cancer-cells-supercharge.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

https://x.com/kimmonismus/status/1978528800401969600

https://healthcare.utah.edu/newsroom/news/2024/12/new-gene-therapy-reverses-heart-failure-large-animal-model

https://longevity.technology/news/life-bio-epigenetic-rejuvenation-transcends-organs/

https://longevity.stanford.edu/the-new-map-of-life-report/

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2794146

This is a pretty crude estimate which ignores a lot of statistical issues. But forme the sake of getting to a more optimistic estimate that applies to my situation, it serves my purposes. If you’ve found any better data sets, please share them!